Review | Great God Grove – Armed With An Oxford Dictionary And A Pack Of Children’s Crayons

Rodney – easily my favourite character from Great God Grove (LIMBOLANE, 2024) – is succinctly the perfect example of what I believe to be most of the game’s strengths to sell it as an experience worth experiencing. Using this elusive and omnipotent canine as a synecdoche of sorts to recommend the game may seem reductive, whereas it is actually a testament to how every moment felt whimsically distinctive and left its mark seared into my memory.

When I first met Rodney, he growled at me like any dog would and pulled a hyperbolically distraught expression when ignored. This interaction was enough to entertain; I continued exploring with an amused grin on my face – the equivalent of a belly laugh when I’m by myself – and was surprised to see an endearingly repeated presence made from this doltishly animated dog.

In Great God Grove, we the player take the role of the Godpoke, the assistant to the gods of the grove, and are entrusted with restoring the tensions among the many denizens of the land caused by the up-and-coming god, King, so that they can work together to once again to stop time and space from being torn apart as per every few decades. All of this is completed utilising the Megapon, an armament that was stolen from King and given to our Godpoke so that we can suck up objects and words and shoot them back out to converse and problem-solve.

Through this premise, Great God Grove attempts to deliver a story-first puzzle game in a tight package that leaves you wanting more (complimentary) thanks to a breezy runtime of roughly seven hours. Having beaten the game, the package was pristine and wrapped with colourful decorative paper and a bow; it left such a strong impression that I hesitate to mention the minor – emphasis on minor – technical hiccups to avoid tainting a glowing recommendation.

Rodney’s oft-available scowls and animalistic mumblings can be removed from their context and thrown at other characters to provoke a reaction, occasionally motivating the plot. Whilst the Megapon and its application will likely be the unique selling proposition to players interested in gameplay, it was still impressive to see that the vocalisations of a random animal were useable for both primary objectives and the player’s aimless musings. It’s a testament to the creativity of LIMBOLANE and the developers accounting for the player’s actions contained within Great God Grove that the game never strained when I wanted to strip Rodney of his fur or use him to insult other characters.

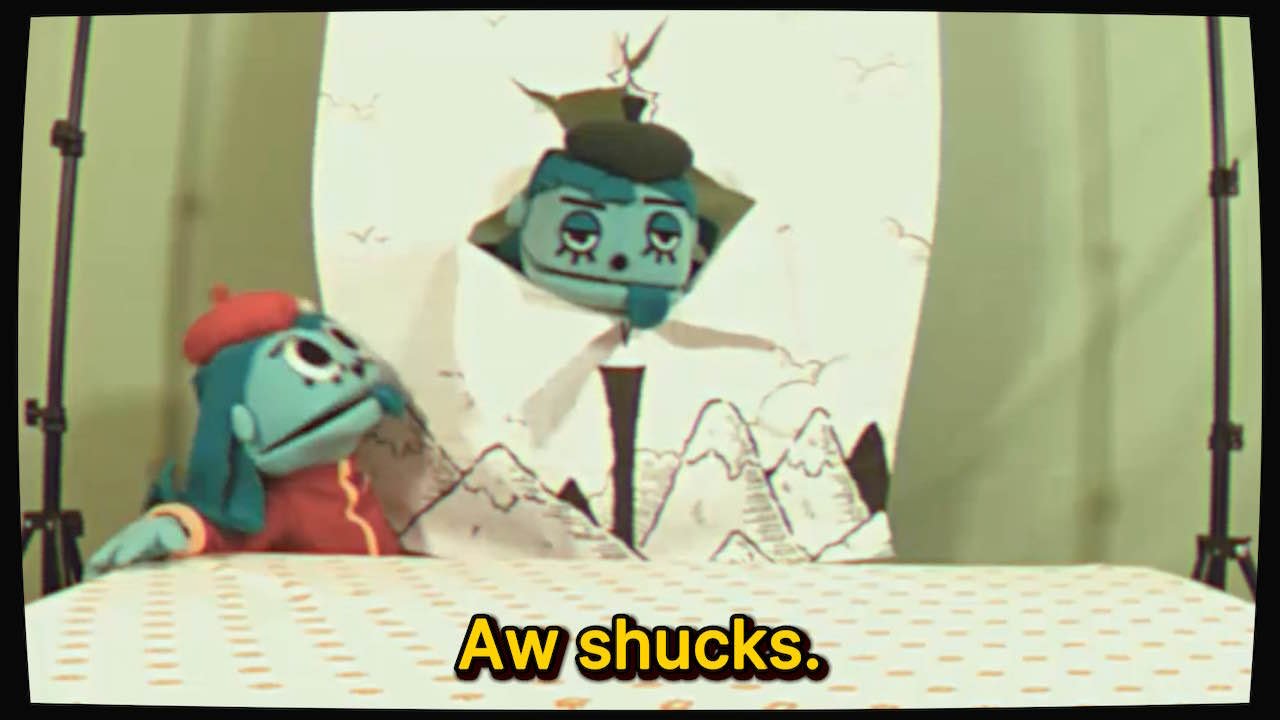

On the topic of stripping Rodney, doing so will expose a photograph of a sausage, flexing the game’s already versatile art style. Similar to the developer’s previous outing from 2019 – Smile For Me – Great God Grove utilises mixed media to great effect. Each of the many characters that occupy the vibrant grove flaunt the talent behind their creation with novel designs and varied expressions; all of them embody the engrossingly estranged vision of their creation with the highlights of the developers’ Spanish art style seen in their graphic novel work. The Bizzyboys, typically portrayed through the 2D-3D art style of the rest of the game, are occasionally depicted through VHS tapes as puppets in the real world. These tapes also take what Smile For Me set up even further, as they can detail character studies of isolated, declining individuals alongside their humorous and nostalgic appearances. Furthermore, the gods depicted throughout the experience are all completely rendered in the third dimension, accentuating their difference in standing from other characters whilst giving them a memorable and powerful presence.

Beyond feeling like a view into a universe where Disco Elysium (ZA/UM, 2019) and Luigi’s Mansion (Grezzo, 2001) are entries in the same franchise, Great God Grove also portrays an alternate view of its queerness and proposes how media, particularly video games, could converse with this part of themselves more maturely. Whilst most characters indubitably exude the demeanour of someone who would eat the pens and crayons that they were beautifully drawn with, they also all express a great deal of dimensionality and relatability.

Characters are often romantically queer and given moments to indulge their relationships with those of the same gender, although their identification doesn’t define them and they are still given the space to struggle with things like existentialism and ipseity. This was a delightful surprise. It feels monotonous and discouraging to see ‘cosy games’ repeatedly fall victim to the same trappings, wherein all characters talk with a resounding grasp of their emotions – as though the financial challenges of covering therapy have never shown themselves – and a character can be entirely described by their lesbianism with the same cadence that another is identified with their long curly brown hair. The full range of this quality can be especially appreciated in the game’s ending, where the themes of artistry, queerness, societal assumptions, and death all tie into their natural cessation.

Whilst I believe that more time could have been given to explore a few extra characters before the conclusion, it is inexpedient to deny that the game’s current runtime allowed the audio-visual experience and narrative to feel their most unusual and arresting. Of the few cracks that uncovered themselves from this gift of a package, the inconsistent audio mixing and the slightly-too-big UI elements when button prompts were left on were the only flaws to make themselves known when playing the pre-release, Nintendo Switch version. If these flaws are likely to hurt the player experience – which they didn’t for mine – then watching the patch notes closely for the coming weeks may be a sensible course of action. Otherwise, Great God Grove truly is the cream’s cheese (its choice of words, not mine) and the developers at LIMBOLANE should be proud of the experience they’ve crafted and how it will surely touch the hearts of many who play it.