Noah Estey Rediscovers An Ancient Antique In Indiana Jones And The Infernal Machine | Winter Spectacular 2024

There are few directors in cinema with legacies as strong as George Lucas. Despite possessing an oft-criticised writing style, Lucas holds such a vividly distinct imagination that has enabled him to connect with audiences all across the globe. Heck, even his forgotten first film THX 1138 has been praised for effects that managed to craft a world visually distinct from our own with a budget under a million dollars. Yet, this was merely a stepping stone in Lucas’ career, as he went on to make cinematic history with his story set in a galaxy far, far away. But while Star Wars is certainly his biggest achievement, it’s not the only iconic creation by Lucas. After spending so much time crafting stories about the future and far-off worlds, he would decide to look back instead of forward, writing a new film about men trying to understand the great powers of the world's myths and religions. I am, of course, talking about Indiana Jones.

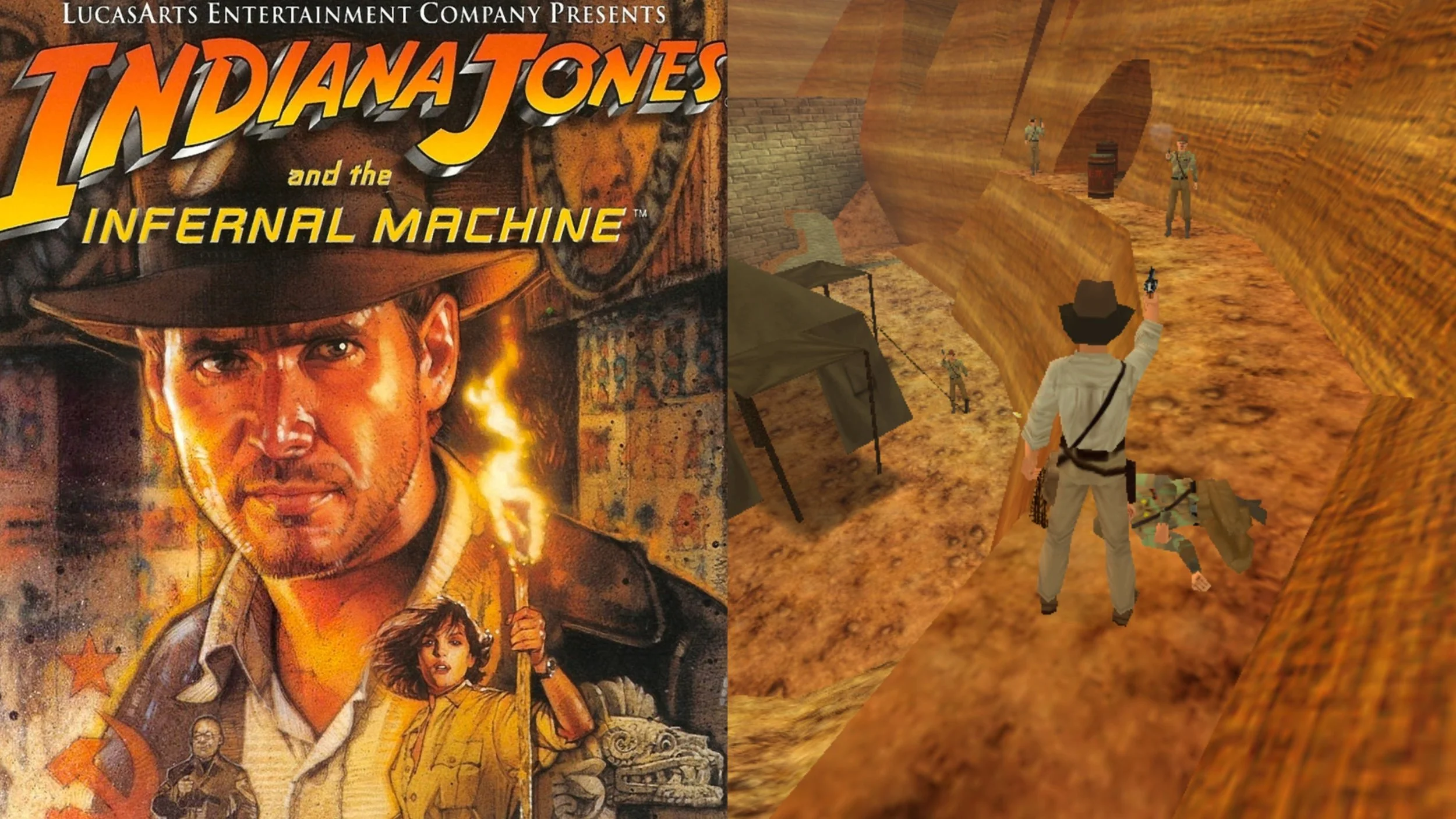

Despite the fame that the character possesses, Indiana Jones games seem to be as rare as books from the Library of Alexandria, causing each announcement to be met with much fanfare. It’s for this reason, I decided to explore a title much like THX 1138, a piece of media that is important in the history of Lucas as a creative but is largely forgotten from its medium's community. This year saw the release of Indiana Jones and the Great Circle, an action-adventure game released on the 25th anniversary of the very first 3D Indy game: Indiana Jones and the Infernal Machine. It is with this game that my journey begins, wondering if I will find a treasure from a distant past, or junk from a bygone era.

I began my expedition by researching the exploits of Dr. Jones. Like many action heroes, Indiana Jones’ first video game appearance would be in an adaptation of his debut film: Raiders of the Lost Ark. The simple Atari 2600 game served as the first of several 1980’s adventures that would find Indy traveling across a variety of platforms, starting with Atari, before progressively developing more releases for the home computer. None of these games were anything worth writing a dissertation on, until 1992 when LucasArts released its first take on the film series, Indiana Jones and The Fate of Atlantis.

Fate of Atlantis was a point-and-click adventure game that separated itself from other entries in the genre by allowing players to choose one of three unique playthroughs referred to as “paths”. These include a team path (where Dr. Jones would team up with psychic Sophia Hapgold), a path of wits (where puzzles are the primary focus), or a path of fists (with an emphasis on action and set pieces). All paths follow the same story, but puzzles, dialogue, and events change depending on which option was chosen. This feature heavily encouraged multiple playthroughs and was just one of the reasons why Fate of Atlantis became a critical and commercial hit while often being considered one of the best games the genre had to offer at the time. It’s no surprise then that a sequel was planned, but due to Germany’s strict laws prohibiting portrayals of Nazis (or in this case, Neo-Nazsi) in entertainment, even if they are the villains, the game was scrapped and its story turned into a comic book.

That wasn't the end of this hero’s journey though, as Fate of Atlantis director (and THX 1138 title animator) Hal Barwood would continue to direct Indy adventures for LucasArts by leading the development of Indiana Jones and His Desktop Adventure. In an interview with The Indy Experience.com, Barwood stated that the title was much smaller than the acclaimed Fate of Atlantis, so for his next project, he wanted to tackle something big, popular, and completely new to him: 3D game design. With a high amount of admiration for the 3D worlds being created by other developers in the late 90s, Barwood would use this new crop of 3D action-adventure games as inspiration to pitch a simple concept to his superiors “Jones action in 3D”. LucasArts brass liked the idea, and development on Indiana Jones and the Infernal Machine began. Alongside this bold step into a new dimension, the game would also see Dr. Jones travel to a new era for the franchise, one where he was not fighting with Nazis but the Soviets instead.

Taking place after World War 2, the game’s story would take place well into the Cold War. As the two leading superpowers attempt to manipulate the world towards communism or democracy, both Soviet scientist Dr. Volodnikov and C.I.A. agent Simon Turner race to assemble a machine built by the ancient Babylonians; one capable of conquering the world. Caught in the middle of this race is everyone’s favourite archaeologist, who’s not embarking on this quest to wield the device for personal gain, but to prevent others from abusing it. To do this, Jones must scour the globe in search of four pieces of what is dubbed The Infernal Machine. It’s a simple but fun story that decided to risk moving away from Nazi conspiracies so central to two third’s of the original trilogy, but thankfully still fits the tone of those films. It actually offers a unique twist on the Indy formulae, as at the end when Volodnikov realises that those who try to power the infernal machine will face the wrath of the ancient god Marduk, while American Simon Turner betrays his partner for the power the machine presents itself with. It’s a fun way of showing a more murky conflict the Cold War adventure created once the more black-and-white World War was finished. What’s more, by travelling all around the world to find the pieces of the machine, the story serves as a good excuse for unique levels that Indy can jump around in. Speaking of jumping, let’s “jump” right into the game proper.

The Infernal Machine starts off with the famous archeologist doing what he does best, exploring a spot in the desert that hasn’t had any human visitors for decades, if not centuries. We don’t get much backstory as to why he is here, but given it’s a tutorial level, none is needed. What we do need though is the sweet taste of adventure. I picked up my controller (something I always use in 3D platformers), and was shocked by how much time was spent navigating through the pause menu, constantly changing my equipment for whichever weapon or item I needed. The pause menu was not the only way of selecting my equipment, but it was faster than using the bumpers to cycle through my weapons one by one, watching Indy slowly take one out, hold it for several seconds, and then put it away before starting the process over again. This is the biggest problem with the game; it's slow, very slow.

This constant pausing and unpausing continued until I came across a gap far too large to jump over. Indy comments that he could whip across it, so with a smile on my face, I equip my whip, hit the action button, and nothing. I used the camera view option to aim at the piece of wood, and still nothing. I couldn’t figure out what to do, but after moving and adjusting myself for several minutes, the camera focused on a nearby branch, and I was finally able to swing across. “Raiders March” played as Indy swung, but even that didn’t recapture my joy.

This was just the tutorial, and I already had to come to terms that I was either playing an Indiana Jones game with limited usage of the whip, or I would have to fight the tank controls and position myself exactly where the game would want me to stand on a consistent basis. The cinephile hoped for the latter, but the gamer would have rathered the former. I made it across the level, dealing with a couple of snakes (it’s funny for Indy to blast one with his six-shooter instead of bemoaning how much he hates them), jumping across valleys, and instead of finding treasure, Indy finds a familiar face, Sophia Hapgold. Hapgold informs Indy that the Soviets are looking into the history of Babylon, giving our protagonist the hook that draws him into this game’s adventure. It’s at this point I had my first big revelation. Whether LucasArts did it by choice or just familiarity, we are playing the spiritual successor to Fate of Atlantis. This meant I would need to examine the game from a new perspective.

When in Rome, do as the Romans did, which in this case means using the original keyboard method to play a 90’s computer game instead of a controller. The difference was night and day as lining up the correct angle for platforming was much faster than before, and cycling through specific weapons was as easy as pressing their corresponding number key. No longer did I waste time cycling or pausing, I was as ready for a fight like a bunch of Greeks hidden in a wooden horse. I then had a sickening realisation, in an Indiana Jones film, I would be a villain.

I hadn’t hesitated to use a controller because I was focused on luxury and power modern gaming experiences, and not respecting the time in gaming that The Infernal Machine was created in. I was no longer frustrated at the game for the time wasted switching weapons or un-equipping them, as that frustration was dedicated to myself for not fully embracing the time capsule that lay before me. I viewed this piece of the past as something for my modern consumption, not my retrospective respect. If I’m going to properly analyse this game, I will need to examine it despite modern gaming experiences, not through them. I play some more, gathering my thoughts with this new mindset.

When separating the execution from the ideas, Indiana Jones and the Infernal Machine feels like the perfect adaptation of the film series on paper, as the films have several tropes that are a perfect fit for an action-adventure game. They are the inspiration behind the award-winning Uncharted series, after all. The game seeks to produce the same feelings that moviegoers had by using three core aspects of the film: action, adventure, and discovery. It successfully recreates these to varying degrees, but let's start with the weakest of the three: action.

Combat in the game is underwhelming. While Indy does have iconic scenes with his revolver, Dr. Jones is depicted far more often as a brawler than a gunslinger, yet the combat sequences strangely treat him more like Han Solo. It's for that reason that despite featuring both the whip and a bare fist option, they're seldom (if ever) used in place of a combat rifle or handgun. This shunning of melee combat becomes especially awkward as Indy gets captured halfway through the game, leading to a stealth section where getting caught puts you back in your cell to try again. Instead of using this opportunity to trick a guard, use your fists to knock him out, then take his weapon like how it might be done in the film, the game makes you sneak past several enemies until Indy recovers his personal weapon. This section really proved to me that LucasArts wanted gunfighting to be the only form of combat in the game, so how is it? The answer, not great.

Despite how much emphasis is placed on firearms, making a shooter didn’t seem to be the priority as I never needed to reload any weapons, and Indy’s iconic six shooter carries unlimited ammunition. Many of the early-game weapons make combat feel repetitive as the opportunity to use grenades, a shotgun, or an SMG doesn't appear until around the halfway point. Coupled with poor enemy AI, combat quickly becomes repetitive as every encounter consisted of me running around the battlefield, spamming the fire button while dodging and killing enemies without much effort. After a fight was done and the dust had settled, I'd swap my weapon back to the empty-handed option, ready to leap and climb over any obstacles that were in between me and my goal. Leaps and climbs that were a bit awkward.

The most important thing to note about platforming in the game is how it works when I needed it to, but not necessarily when I wanted it to. Controls are responsive and anytime I fell off of a ledge instead of jumping, it was a direct result of user error. The big issue with platforming was how I needed to take several seconds to line up my jumps as any ledge I caught at an angle would result in me falling to my doom, a fall that would cause me to pray to Marduk that my last save was a recent one. While I did adapt to the process over time with improved jump accuracy, it was still a tedious process that’s not what I expected from an Indiana Jones game. So with two points that are a bit lackluster, is there anything worth salvaging here? A puzzling question with the answer being… puzzles.

The game decided to use the pedigree LucasArts is known for to its full advantage, separating itself from the other entries in the genre with a large emphasis on puzzles. Despite Infernal Machine being his first 3D title, Director Hal Barwood showed his expertise in the adventure game scene through the usage of objects interacting with their surroundings, as well as the subtle ways that Jones may give a hint to a puzzle’s solution. Modern game design often beats players over the head with hints, so Indy's sparse but helpful words mean the immersion the game provides serves as a relic lost to time. Details matter, especially when those small details add up to more.

Throughout my playthrough, I found many similar details that helped improve my experience. Some were fan service, like how Indy will appear in both his iconic film looks (with or without his jacket) depending on the environment. There were also more subtle details, like the way the rungs of ladders matched Indy’s feet when climbing or how trudging through shallow water was slower than walking on land. My favourite little detail by far came in regards to interacting with objects underwater.

While on land, Indy may say “It’s locked” or “I’m sure a large vibration could tear this wall down”, but underwater he will be shown forcefully trying to pry open a door to no avail. LucasArts realised that having him speak while underwater wouldn’t work, so it replaced words with big gestures, and it conveys all the information needed: “I can open this, but not yet, so maybe instead I should check out that crashed fighter plane close by”, all with a single gesture. It really shows just how much the team cared about crafting this adventure. But when people think about adventure, they don’t think about words or movements, they think of exotic locales and interesting places, a presumption that LucasArts definitely delivered on.

Desserts, forests, jungles, an Asian monastery, mountains, and a volcano are just some of the locations I found myself in throughout this journey. While some themes may repeat (such as rivers), the colours and object designs used really helped transport me to another part of the planet. One moment that really stuck out to me was when I was journeying through a dangerous volcano, spending the entire level constantly jumping over small rocks, knowing that any miscalculation would result in a swim through some magma. After what felt like over an hour in this hostile environment, I exited the volcano and was greeted by a lush beautiful jungle. With only 64 bits, the game was able to leave me more awe-struck in that moment than any “next-gen” title I’ve played this generation. It’s really a credit of using a little to accomplish a lot, as all this wow factor can only be achieved through solid immersion. However, visuals are only one half of achieving said immersion as the other half is sound.

Adventure games are host to some of the medium's most iconic songs, which is interesting because Indiana Jones and the Infernal Machine doesn’t have a lot of noteworthy tunes. Levels are infused with various sounds, whether they are the natural chirping of birds, the harrowing winds coming down the mountain, or the intrusive engine noise of Russian machinery. It was because of this that I was constantly allowed to be in the moment with Indy, facing both fear and excitement for whatever may be lurking among the uncharted environments we found ourselves in. Furthermore, it also gave the game a more film-like quality as every piece of music that played felt like an establishment shot; short, used upon entering a new area, and most importantly, cementing the tone. It's such a great use of songs as many new games rely on cutscenes or the dreaded “squeeze through the wall” to inform players they are entering a new section, yet Indiana Jones accomplishes it in such a simple but effective way. As a fan of the films though, I’m delighted to state that “Raiders March” often accompanies Indy when he is swinging across a gap, so even though I wasn’t excited the first time I heard it, I did enjoy the other times. It’s a shame that despite all of these little touches, my overall experience was still a mixed one.

The title has a lot of charm, especially for those willing to really look for little details and flourishes, but I still stand by my criticisms of the game being a slow-paced adventure that left me a little disappointed. Indiana Jones films are incredible journeys and despite The Infernal Machine's best efforts, the stop-and-go nature of it all often left me longing for the speedy exploits of Nathan Drake. This slowness really presented me with a dreary feeling that would slowly infect my impressions of the game over time. At the game’s climax, Jones gets transported to a completely different world, one where the artists are able to go all out in creating things that we haven’t seen anywhere else in this game. When this new world of opportunity presented itself, I had no interest in running around and exploring the corridors and mysteries (including a fun Monkey Island Easter egg), I just wanted to get out and see the destination of this journey.

So looking back after 25 years, does it hold up? Not really, but honestly, it’s better this way. Indiana Jones and the Infernal Machine really feels like part of a bygone era of gaming’s past, one where maybe the medium wasn’t as clean as it is now, but still has some things worth looking into. It was a time of risks and rewards, one where developers were still trying to figure out a secret formula that upon discovery, turned so many modern games bland and lifeless. It is for this reason that in an era of re-releases, maybe we end up treating games too much like artefacts, touching up their flaws to look nice, but losing the history they contain in the process.

It’s for that reason that I’m glad I went on my expedition through Indiana Jones and the Infernal Machine, as the adventure stands as a testament to 3D game design and history. It’s also for that reason that I find the designation of treasure or junk not as appropriate as antique; an old, possibly obsolete object that may still hold a lot of value depending on the degree to which someone cares about it. But hey, if you think it belongs in a museum, I won’t argue with you.