Review | Lunacid - In The Shadow Of Alucard

Symphony of the Night, as in, the subtitle of the game famously prefixed by the word “Castlevania” which, itself, a different word, implying a whole genre’s fixation of aesthetic and gameplay values – most of which circles a drain that goes to a landfill that is somewhere both meaningless and entirely descriptive - released in the late nineties. It wasn’t a sleeper hit by any means, many publications revisited it soon after release and put it in meandering Best Games Of, lists.

Deep down here.

It hovered over the world like an ancient dragon: sometimes untouchable, altogether mythical. It inspired countless discussions in places like The Castlevania Dungeon Forums, which you can still visit today. Symphony gets name-dropped a handful of times a week. Itself as bizarre as any Inverted Castle depicted in the series, The Dungeon Forums is requisite with Fan Works, the most and still populated board where once a week a guy who makes pixel art/MIDI music/one single drawing a year produces a thread outlining that They Will if not release a fangame the size of Symphony of the Night, they might at least fly high enough to glance off of Castlevania 2: Simon’s Quest.

Death is for the living.

A twisting, white fog has enveloped the world since. Death, disease, discomfort. A type of legally specific public violence is at an all-time high, and the world we want to respect carries a loaded gun. The most unfortunate parts of our society litter the streets with nowhere to go, no shelter, no safety. Everything twists in on itself, the children of Symphony of the Night stretched themselves into bizarre cartridge shapes. A pattern of musical annotations like Harmony tried to sell players on the idea that there could be a follow-up, but seldom did saviors arrive.

Does the word metroidvania mean anything to a person on the street? Does it mean anything to you but a tag on Steam, a word choked and brought down by anchors of nostalgia that we could be taken somewhere else again? The past is alive in us, if only in the blood and pixels spilled to make a video game. The Virus of if all cuts through in strange, oblique ways. Critics invent new words, Souls Like, or even claiming something is Like A Rogue to cry out to prospective buyers what a videogame has to offer.

Hello there.

LUNACID, released March 2022, is about a world poisoned with miasma choked up by a mysterious beast, but is also about the Hole in the world the mystics, thieves, and criminals have been thrown in. An ecosystem and world of itself – it is every grain of sand and brick tile underneath our foot as players in this world. A stamina-based dungeon crawler and first-person sword game, there are lots of words that can be used to describe Lunacid in a way that tells prospective buyers if they should be interested in it or not.

I believe, in my heart, that most of life is a lie told to us by the people around us who care for us, that words like “Metroidvania” and “Soulslike” are general descriptors that mean something to the kinds of people who say them over and over again only. What I know about Lunacid is that already, all of the secrets and inspirations about it can be divulged on one wiki or another. What I know is that through the humming and crystal teardrops of the soundtrack, a sense of almost insecurity permeates every area after the first handful. These community, collaborative soundtracks never quite match the intensity of someone in charge.

Oh, this is a Michelangelo-like.

If the games of Fromsoftware were dictated by a particular aesthetic, it’s one only visible in retrospect, so, trying to capture it is mostly a fool’s errand: Item descriptions and cultural references happened first in Castlevania and that might be part of the cloth all of these games draw from – LUNACID is no different. Players will jump and slash their way through an assortment of levels, because they are tied together in a way that resembles Levels, with swords and bows and daggers and spells, with a buzzsaw-like efficiency that returns to games like Ys III.

Like the grandfather and it’s misshapen, cruel offspring, LUNACID boasts a stat system that at most times feels fit to curb difficulty, but that accrues at the same street-car speed as the player journeys through the castle The Well. It is a soft mattress that we might leap from balconies onto, always there to catch us. Of course, there are other stats, too.

Would you love me if I was….

LUNACY is the driving force behind the interest the game has: spells wax and wane with the passing of the moon, and the numbers that can be called “LUNATIC” drive themselves up with consecutive spell use. The higher they go, the more damage offloaded on the player, and the more spell damage is caused to a variety of Large Snails and Haunted Ghouls is dealt. It’s a novel idea, but doesn’t stick around with a hand on your shoulder. Saving resets player LUNACY every time it’s done, like a backhanded compliment that creates a path of an ideal playthrough in the head. There is almost no commitment to whatever ideas might separate it outside of a “SOULSLIKE” tab on many online digital platforms. If there were, who could say? A certain kind of maximalism is already present – maybe further iterations might improve on the clandestine secrets and the strange might go beyond a vibe.

I wait for a challenge in this abyss, screaming at the sky that’s been taken from me like a bird with broken wings. Swords, guns, bows, spells. All of the little trinkets I need to have a good time, and for what?

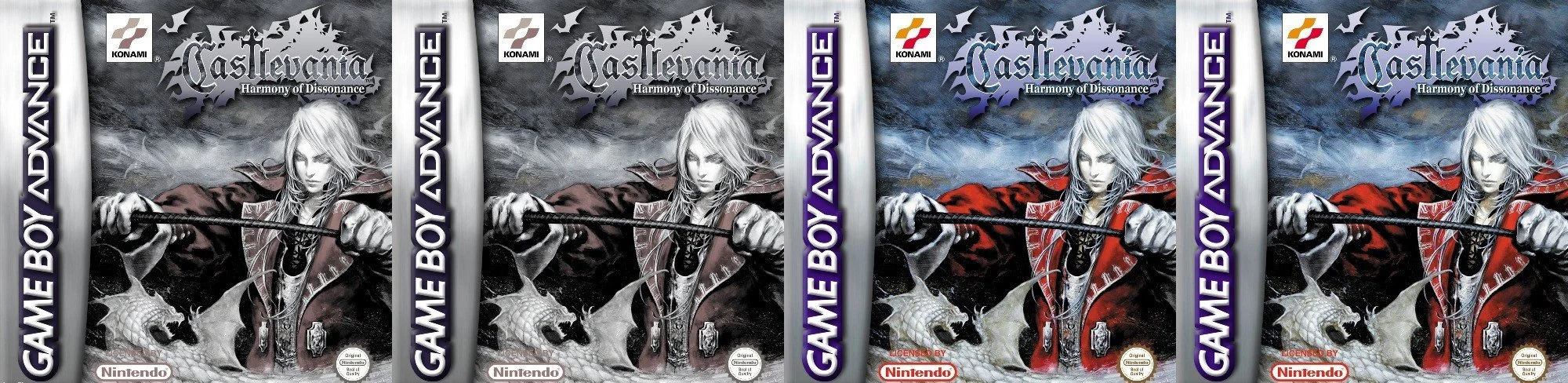

LUNACID is worth EXACTLY TWO COPIES of CASTLEVANIA: HARMONY OF DISSONANCE out of four.