Review | Mothmen 1966 - The Stuff of Nightmares

Mothmen 1966 is highly aware of its origins in trashy books. It comes from both guides to the paranormal and fear-of-the-other fiction written in the mid-20th century, and writing in the latter half of the 20th century that mined that work for plot. It's Stephen King territory, a story of American terror that takes place on a bad date at a gas station during a meteor shower. It points out to the player via its characters that the authors know this is the case, this isn't something "out of one of your cheap books," as the old gas station attendant says to the author caught up in the monster story with him.

The game asks you to approach it on those terms, to buy into the inner worlds it lays out for its lead characters, yet not take it seriously enough to criticise it. There are Mothmen here somewhere too, within...we're just waiting for them to come along. Is that one above the trees?

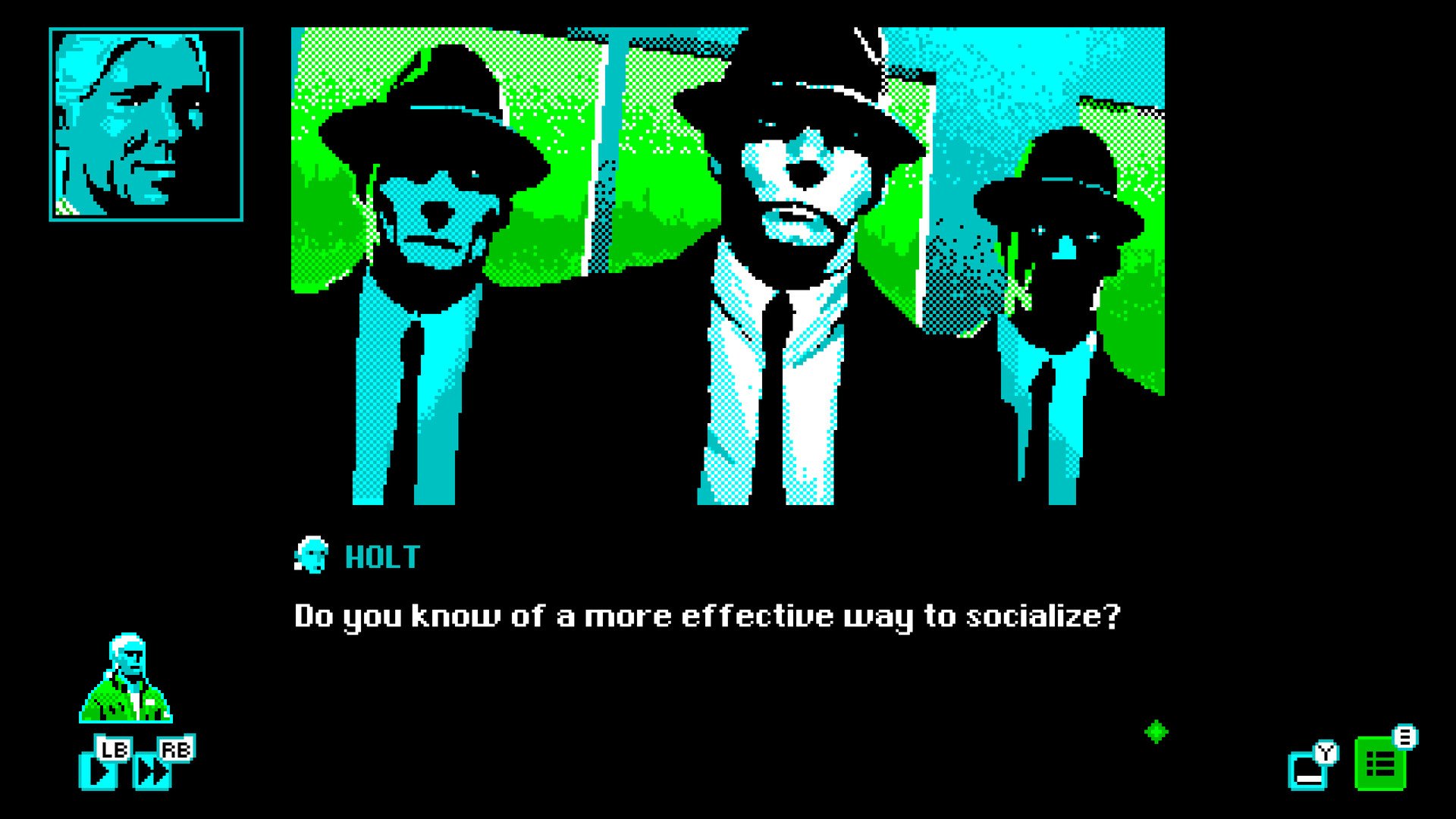

These guys seem trustworthy.

Meanwhile, over ten chapters, each spent inside the head of one of the three playable characters, you see terror in Victoria over an unexpected pregnancy, trauma in her partner Lee over his father's brutality, and paranoia in Holt, the gas station owner over the visits from strange men and odd dreams. There's also Lou, the author, and you experience his constant lack of portrayed interiority just as strongly.

Lou is also the only black character in the game, and the only other human NPC unaligned with something supernatural. He is the fourth lead, the one most knowledgeable about the incidents happening, and also the one who is made into a joke, who is verbally assaulted multiple times, and who seems to have no reaction to those moments or stakes attached to his life.

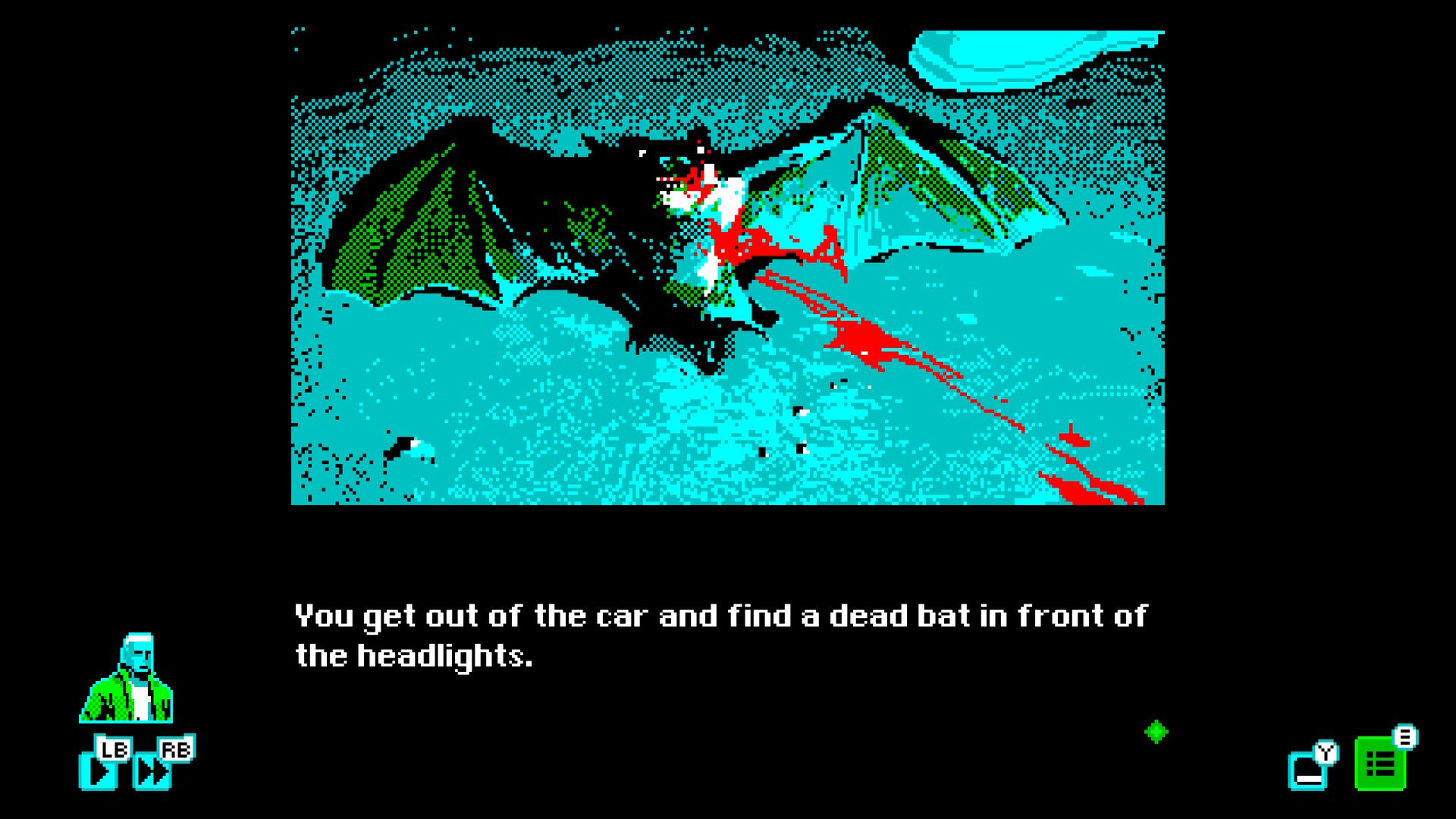

It is a bat, man!

With all the awareness of the genre's tackiness, the spookily deployed tropes, there's no inclination to unpack things that lurk within that, like that inclination to marginalise Lou's role. The choice is made to reinforce pulp horror's conservatism, and, unlike in the rest of the game, there doesn't seem to be an interest in commenting on this genre trope.

For instance, the game features prominent inner-monologuing from Victoria over her experience of an unwanted pregnancy with her livewire boyfriend Lee. The game sets up a delicate and emotionally complex situation, in the second person, in which you learn that you have considered having an abortion, that you are feeling shame and guilt about your feelings and you need to share this with Lee. You never get to do so, however, not in that way. Victoria never gets to either complete the thought about this or react to the outcome of her circumstances, as the game's final action neatly allows her, and you as her, to accept benevolently the role of motherhood.If this is a clothed critique of how White American ideology has a staged level of who it allows interiority and initiative, and how much it permits before it gets angry, then you can congratulate the game, as it fully manages to emulate the structural horrors of limited institutional imagination. This was how Stephen King came to see his work after all. However, with how eager the writing in Mothmen 1966 is to show off its self-awareness, you could also be excused for finding it lazy, predictable and even disquieting.

The crux of the game's action is American Civil War weaponry that communes with the gas station owner via a ghost, in order to allow it to kill bipedal meteor creatures, the 'Mothmen' of the title. In fact, it's a total revision of the technology used in that war over enslavement in America, the machine gun, and its purpose. There is no interrogation of how the game's monster narrative, which is about a mystical genocide, connects with this. There is no investigation either of the invoking of an indigenous group when talking about a man who lived in the hills shrinking animal heads as art.

The three main characters.

It's like the way that plenty of beloved 1980s movies always feature some kind of social conservatism or shock degradation of minorities deep down in their bones. Mothmen presents itself as a deconstruction of these 40-year-old pieces of media, but neglects to do much more than a surface-level examination of their narrative contents while imitating their style.

The slick and smooth text-choice gameplay that connects your decisions and the graphical story in the dithered images during puzzles is impressive, but those puzzles themselves are about as fun as the story. There's one of these moments per chapter, and these can be laborious enough to make you want to quit playing, which captures the experience of old-school interactive fiction well enough.

At the end of the day, the major thing going for Mothmen 1966 is its visual appeal. The images are a combination of those that would accompany this story in the 80s via a limited palette computer screen, with the skill of a graphic novelist's framing, and they are often very compelling, dramatic and brutal. This could have been a great and engaging feat of visual storytelling, harnessing a history of computer art in ways that do build on history, if the written story didn't do so much to unravel that power.

Mothmen 1966 feels like something that could have been written at any point in the past 50 years and seems to intend to be that way, to an end that is deeply disappointing. Here, another America that never existed, another one that wipes out the social history of the nation, and replaces it with a Mothman t-shirt you forget buying.

You have give Mothmen this. It is a killer artstyle.

![Review | A Juggler's Tale - There Are No Strings on Me [Pumpkin Spice 2021]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5caf2dea93a63238c9069ba4/1634216368514-8XELF6ZDGL6H64XO3GJT/juggler%27s+0.jpg)

![Review | Chasing Static - Escape To The Countryside [Pumpkin Spice 2021]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5caf2dea93a63238c9069ba4/1634584671352-68DKTJVLD2YH94IK2J2K/chaising+static+0.png)