Getting Over It With Madeline Blondeau: Five Silver Linings in 2024 Gaming | Winter Spectacular 2024

2024 was rife with remasters.

Assessing these re-imaginings, retreads, and what have you, felt fruitless at year’s end. Persona 3 Reload, Final Fantasy Rebirth -- exciting, but still built on decades-old bones. Silent Hill 2 is by my favourite horror developer in the game, but really, it was hard to justify the $70 out of pocket for a game whose surprises lay in the mechanics of the 2001 original. Sonic X Shadow Generations included a new Shadow game, but most of the package was still taken up by a fourteen-year-old game.

Out of the lot, Tomb Raider 1-3 Remastered was a lovely facelift, and I spent dozens of hours with it. The photo mode was a delightful feature, and seeing fully remastered 21:9 versions of the levels I grew up with was borderline magic. That said, the collection also managed to literally break games that worked since the mid-’90s with strange physics and bugs. Which is almost impressive, in its own way.

So 2024 didn’t feel like a particularly original one for the medium, in a popular sense. Aside from this – most of what I played wasn’t from this year, really, but release years matter very little in this day and age. A game can ship a mess and garner esteem after three years of patches, still in the zeitgeist and conversation.

But it also felt disingenuous to just play older games and talk about them on Lexi’s website for a year-end project.

“Hey, are you doing year-end stuff? Can I do that?”

“Sure! We’d love to have you.”

“Great. So here’s my write-up on Fractured But Whole and The Last of Us Part 1.”

“Mads, I… Hm.”

“I just got around to Doom Eternal…?”

“... Why did you ask to do this again?”

Yeah, that's about how it would go. That just wouldn’t be right.

So outside of one title, I tried to focus exclusively on new games that truly stoked my imagination and curiosity this year. Projects that challenged my perspective of certain genres, bowled me over with a unique style, represented a sense of mechanical or aesthetic transgression, or some amalgam of the three. If you feel as stifled by both the mainstream and indie spaces same as I have, think of this as an antidote.

Children of The Sun

Less is more. Children of the Sun wields its brief runtime like a bolt-action rifle. Players take the role of a young woman whose family was taken by a sinister backwoods cult. Now she stalks the woods around their compounds and outposts in a mask right out of The Strangers. Along the way, she relives sexual trauma in nightmares and masturbates in bathrooms while she cleans her gun.

She’s armed with a rifle – only a rifle. But one bullet is all she needs. The player takes control of her shots in a mechanic that blends Max Payne with the 2008 James McAvoy/Angelina Jolie vehicle Wanted, but leaves the balding, flaccid machismo at home. Told in spoken dialogue and sparse typed sentences, Children of the Sun doesn’t overstay its welcome and never runs out of things to do with this central gimmick. With hard-edged stylistic cues drawn from late-era Grasshopper – and arguably the most accessible control scheme of the year – it’s unlike anything you’ve played. The main loop evokes disc golf and Karl Fairburne in equal measure.

Children of the Sun challenges many long-held assumptions about games. Do we need as much exposition as we’ve grown accustomed to? Is “more story” really “good story?” And does a shooter need to throw as many mechanics as possible at the player to offer the raw, intimate, sexual thrill of cranial penetration? The mind wanders, as does my bullet.

If “Game of The Year” means anything to anyone anywhere anymore, this is probably mine.

Sprawl

It’s not Strafe, it’s not Stray – it’s Sprawl. But really, what is it with the “S” [consonant] “R” titling schemes?

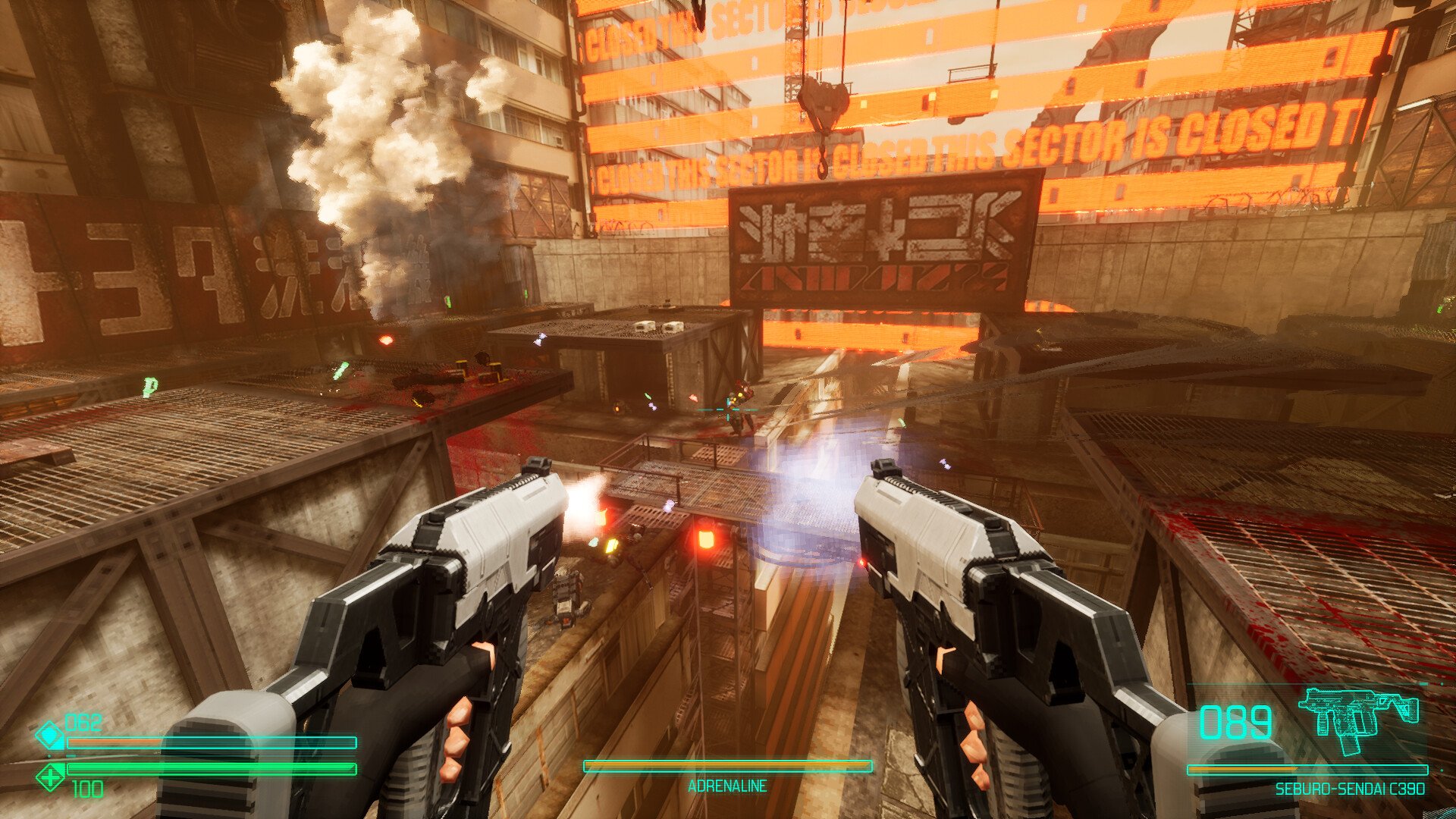

Sprawl is old-school without proclaiming, very loudly, how old-school it is. As they draw from early aughts shooters like F.E.A.R. and parkour-based runners like Mirror’s Edge, Hannah Crawford and Carlos Lizarraga arrive at something refreshing and original when held against the contemporary ‘boomer shooter.’ Aside from its pensive and speculative narrative, the mechanics demand a finesse and precision that demands quick deaths and faster respawns. Instead of an endurance trek through bloodied corridors, Sprawl serves up a collage of mise en scene designed to reward player ingenuity, speed, and stylistic flair.

In that sense, Sprawl is spiritually kin to unsung acrobatic shooters Stranglehold and Wet. But where it pushes past those – and its own stated influences – is in its bleak authenticity. Crawford and Lizarraga never let the player forget that they are as fragile as they are lethal. Instead of becoming the ultimate killing machine, the decommissioned cyborg protagonist must instead use her assets to kill fast, kill smart, and kill in mid-air. This fragility, when combined with tight air control and uniformly excellent shooting mechanics, makes for a tense and tight faceplant to lead.

Angel At Dusk

Sin has been eradicated. Flesh has been forsaken. Desire deconstructed, gender and sex unified. Now, we are all angels at the world’s twilight. Or is it a new dawn?

Angel At Dusk is part shmup, part hack n’ slash, all eldritch abomination. The game is marinated in viscous fluids and slime, its enemies' sensual nightmares that blend the erotic with the grotesque. Seasoned shmup players will have their work cut out for them, as the game’s jokingly coerces them into harder difficulty levels as it explains its mechanics. The game feels right at home for me, a genre fan who enjoys flying up close and personal to enemy units. Here, the mechanics are built around that gameplay style, and it gives way to an exhilarating twist on a familiar style. A unique progression system – alongside a more traditional arcade mode – incentivises replays for more units, upgrades, and higher levels of challenge.

The challenge of making a new shmup in the 2020s is that, ultimately, the wheel cannot be reinvented. How else can veterans innovate aside from new aesthetic dressing, shot gimmicks, and raw difficulty? Ultimately, it takes a young, independent developer such as Akiragoya – like Zun before them – to show established houses one way they might evolve. Angel At Dusk reframes not only the challenge and approach of the shmup but the raison d’etre as well.

Would you still fight, knowing there is nothing left worth fighting for?

Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door

This year, I got my first video game tattoo. I’d told myself I wouldn’t do it. And if I did, I told myself I wouldn’t just get a character I liked. At the top of the year, the idea that I’d be bleeding out a Mario character on my bicep would’ve made me laugh. “Cringe,” as is parlance.

That was before the remake of Paper Mario: The Thousand Year Door. To say nothing of the game itself – a colourful, intuitive confection – Intelligent Systems delivered the definitive version of a character long since given the shaft on both sides of the Pacific. In the Japanese original, Vivian was a play on okama tropes – “She looks like a girl, but she's really a boy,” read her party description. When brought to America in 2004 – the year Bush endorsed a gay marriage ban – all evidence of her queerness was smote from the English record. Vivian was a cis girl. Open and shut.

On Nintendo Switch, that’s finally rectified. Vivian being bullied by her sisters is more specific, less general context fully restored. Further, her in-game description – “she has a boy's body, but the heart of a girl” – more closely reflects my own understanding of transness. I am not a cis woman. I do not want to be a cis woman. I am more than okay with people “knowing” I’m trans. I just want being trans to be okay, and for people to get off my dick. Y’know? That’s why Vivian resonates. She’s just a funky little girl trying her best to not be a boy, and for that to be in a Mario game is a substantial moment.

Which is why I got the tattoo, see. 2024 is an awful year for trans rights. But it’s a great year for trans awareness. I can’t think of a better character to take with me into 2025 than this pot-bellied little lass.

And the game’s great, too! Remasters are okay if I like them.

Stellar Blade

By some measure, Stellar Blade is a resounding loss for a decade-plus of gamers who advocated for female characters that don’t look like sex dolls. They were always going to lose the battle, of course, but it was a nice fight – and we finally got some alternatives out of it. Yet there will always be a demand for well-endowed femmes in bodysuits kicking ass. It’s a cherished, eternal truth of the human condition.

But as far as sexed-up adrenaline circuses go, it doesn’t get much more weighty and speculative than Shift-Up’s ambitious Nier:Automata wannabe. What the South Korean mobile game developer has put together here is nothing less than a showstopper on par with Sony’s in-house best. It’s an effortless blend of Uncharted, Bayonetta, and (yes) Nier made with the utmost reverence for everything it uses as an influence. The fact remains that when it comes to the global gaming market, South Korea has not gotten a chance to prove itself with a major player like Sony behind them. We accept obvious influence in major titles from other, more establishing gaming hemispheres without decrying them as rip-offs – why not here, too?

Especially when Stellar Blade ultimately does so much more than homage. Its influences are pitons for Shift Up to weave their ropes through, sure, but they don’t define nor lay claim to the climb itself. That’s defined by the mechanical finesse, decadent fidelity, and rousing aesthetics the developers arrive at. When assessing the sum total of the game’s parts, it’s impossible to pin it to any specific one. Because Stellar Blade is recklessness embodied, a defiant and energetic assault on the senses. Relentless, it pelts the player with pent-up fervour, passion, and ingenuity until they can do little but admire its carnal feast of bloody violence and shiny sex appeal.

“Man, they don’t really make games like that anymore.” They do now.

Contra: Operation Galuga

WayForward didn't quite hit the notes of Contra 4, but then - it's not 2007, I'm not in middle school, and my DS Lite may very well be corroding in a dustbin somewhere. Truly, this is about as good as a new entry could get. The seasoned developer provided a rousing, rollicking collection of levels that felt like a veritable jambalaya of tropes from games past. Hard Corps and Contra III are leaned on heavily here, with dashes of Shattered Soldier and a deep reverence for the original.

Where it impresses most is in its willingness to expand and experiment. There's less rigidity in shooting and platforming, with much more freedom and versatility given to manoeuvre the world with. It's still a brutal game, alleviated by a slick progression system that unlocks perks between runs. Players aren't necessarily expected to get through levels in one go, as the game anticipates frequent deaths in a persistent credit system. This is a great way to not discourage players while also not sacrificing the level of challenge integral to a true Contra experience.

While I do wish we got another taste of the isometric Saturday morning cartoon chaos of Rogue Corps, Galuga manages to straddle a line between that game’s tone and the mechanical precision fans expect. With any luck, this won't be the last deployment for the Contras and their mismatched cohort.

I’ve no meaningful insight nor salient wrap-up here. 2024 tested a deeply held conviction for many. “If we believe in and love each other enough, the bad times will end.” But there's a captured market intended to keep us in despair - gambling apps, VTubers, mental wellness scams. Isolated but comfortable enough to not move. Pollyanna Toll House chocolate chip yearnings for togetherness will not break, shake, or gun down the establishment.

Yet my hope is not gone. I love and am loved by too many to feel that way. The world is bleak, and it’s getting bleaker. But if we give up on each other, we give up on ourselves. We can’t give up on each other’s art, either, and artists can’t give up on things that won’t turn a dime. These are often the only forms of catharsis we have against institutional bodies that feel infinitesimally larger. Small cuts and leeches to bleed the illness out. Self-harm and mutilation, vindictive violence. These can shift the scales, and turn the tide like so many cycles of our mother, maiden, and crone.

We fall together. Art – parachute and pavement. See you in 2025, or as we're calling it in my house, The Year of Luigi Part 2.