Game Advertising: How has it changed?

Adpocalyptic

In the modern gaming community, player choice has never been greater. Countless indies, remasters and hype trains await your cash. How all these things are being sold to us, however, has changed massively over the years.

Video game advertising has followed that of movie advertising; multiple trailers released at key points along its marketing cycle, each designed to draw you in and further commit you to the idea of the game. I know what you’re thinking, “Yes, I also took BTEC Media Studies, get to the point!”. Well, game advertising can be done well or terribly. Either remixing an old classic, or crying like an anime fan on prom night.

The ‘Cinematic’ Trailer

The so-called ‘cinematic trailer’ very rarely has anything to do with the finished game. Often these spectacles come up to a year prior to the actual release date, and feature a complete short story (or at the very least, a set piece) from within the world of the game. We get one like clockwork for nearly every AAA title, and it begs the question; what is their purpose?

No other medium does this. The average trailer for a film is typically a cut-down version of the narrative, nothing more (unless you’re a Fast & Furious spinoff, in which case it’s the whole narrative!). A cinematic trailer for a game, however, is an extension of the most un-interactive aspect of the whole medium; a cutscene.

Sometimes, the opening cutscene of a game pulls double duty as both prologue and advertising, which is precisely what Netherrealm studio’s most recent release Mortal Kombat 11 did. Good to see the spirit of recycling is alive and well.

In the current age of five-seconds-then-skip adverts, cinematic trailers display an unusually high degree of effort (even though it is often these very trailers that you end up skipping!), hence why they are mostly reserved for large conventions in order to throw more fuel on the hype fire.

If you want a reliable repeat offender, look no further than the Assassin's Creed series. The franchise now has 11(!) entries, each and every one preceded by multiple trailers churned out by the well-worn gears of the Ubisoft marketing machine. BUT, they introduced me to Woodkid, so swings and roundabouts.

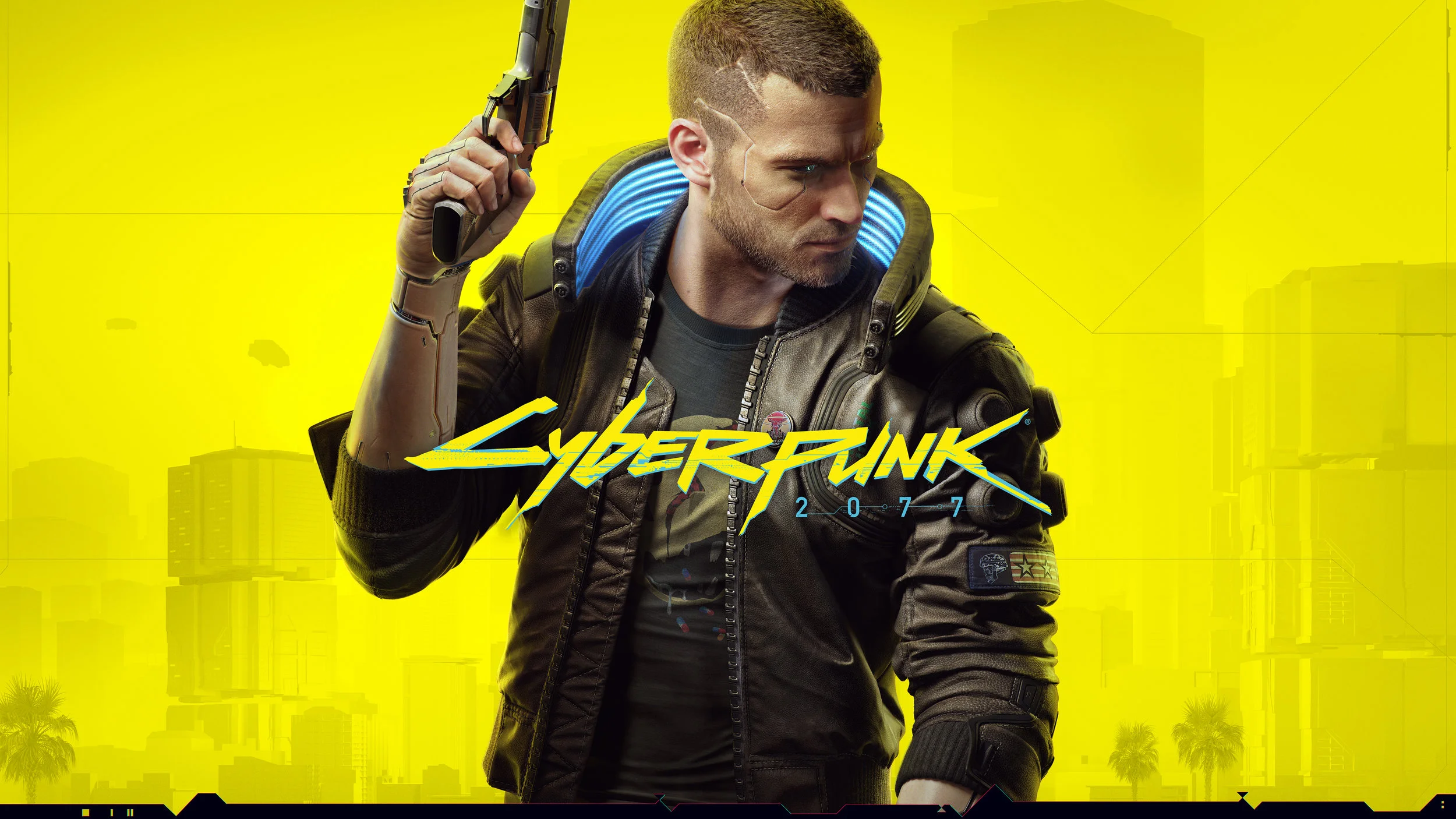

Take this trailer for CD Projekt Red’s upcoming Cyberpunk 2077. It was uploaded nearly five and a half years ago, but still some of the elements are consistent with what we saw during its recent showcase at E3 2019. Those freaky fold-out arm blade things, for a start, and the logo is pretty much identical to the most recent one save for some extra shading. But the point was to sell the world, the tone, and the overall setting. I wonder if they knew they’d have Keanu back then?

To give an example of a cinematic trailer doing its job, the recent Deathloop E3 Reveal has got me quite excited. It’s purely cutscene, only the vaguest of story hints, but I’m looking forward to it; this is the strange territory that the cinematic trailer occupies.

It is fertile ground for your imagination to run wild and see the concept for a game in all its ideal glory. In hindsight, because of the detail that cinematic trailers lack, they’ll always look a little bit silly. As first glimpses go, Deathloop is a perfect example. The actual game could be awful. We don’t know. But for now, we can be reassured by a well-made, promising trailer that shows us what we want to see.

The ‘Gameplay’ Trailer

This is more like it! It’s why we’re here, the meat of the experience. Only in the last few years, the triple-A sector has been rocked by numerous controversies regarding the accuracy of the ‘gameplay’ trailers that have been released. Even as far back as the first WATCH_DOGS, gameplay validity has been called into question.

With certain companies, it’s become something of a running joke to see how the graphics and mechanics have downgraded since their glossy show-off during the marketing cycle. This is the trailer that most closely resembles movie trailers, as it’s a mishmash of both actual gameplay and scripted cutscenes.

However, this trope in itself has eroded. Nowadays we just see the entire chunk of showcased gameplay released in one go, often titled a “gameplay trailer/reveal” but is in fact 20 minutes long. Give the people what they want, I suppose. But when you can control what the people see, everything becomes a lot easier. It is great fun when you can hear the ‘players’ over-enthusiastically speak to each other over fake microphones.

Mobile games are an exciting new facet of the gaming community. Sure, some of the games are derivative cash grabs, but who are we to talk? (looking at you, steam store). But the adverts. My god, the adverts. Some are hilarious, some just terrible. Like using Kate Upton to sell Game of War, or Liam Neeson to sell clash of clans. My personal favourite is when they get someone to record themselves in the corner of the screen and fake-react to the gameplay, giving us a perfect disconnect and a good laugh.

In this cynical age in which we live, audiences are giving both publishers and developers less credence than ever before. They’re having to work harder to win us over. And in this untrusting new world, cinematic trailers give us a comforting glimpse into what could’ve been, gameplay trailers show us what we got instead, and mobile game trailers show us what we never wanted in the first place.